I’ve been a professional writer for 22 years. The first time my writing was published was in 1993, when I was the circulation manager for a small weekly newspaper in Detroit. The full-time reporters considered the job of writing death notices to be beneath them, and shoved it off onto me.

I’ve been a professional writer for 22 years. The first time my writing was published was in 1993, when I was the circulation manager for a small weekly newspaper in Detroit. The full-time reporters considered the job of writing death notices to be beneath them, and shoved it off onto me.

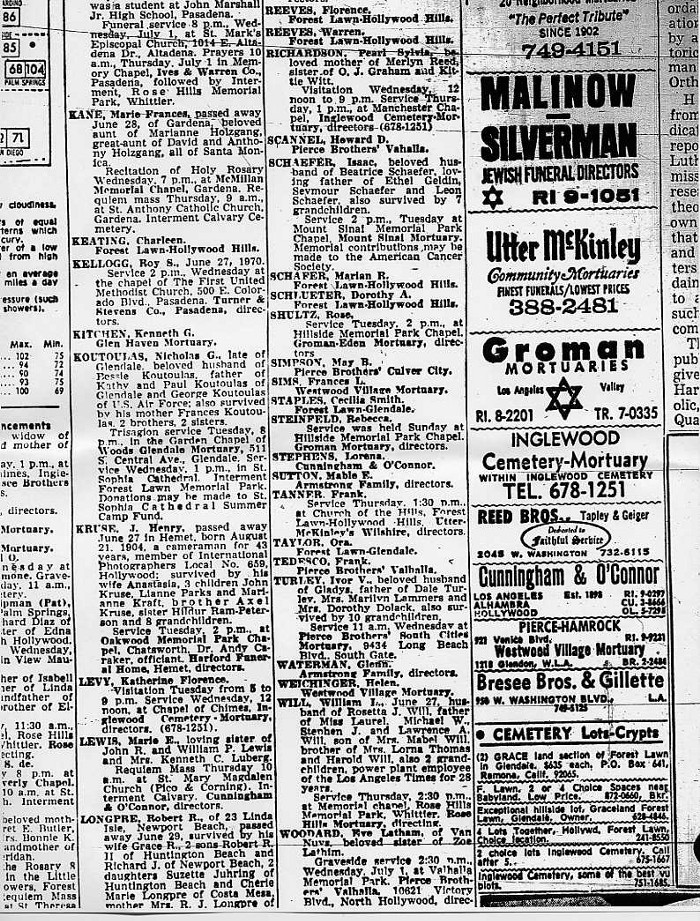

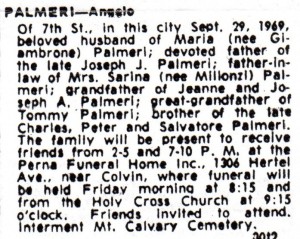

I loved it. Each week, the death notice forms would come in from the funeral homes, along with the remembrance ads from the spouses and loved ones of the recently, or not so recently, departed. Some notices stuck to just the facts: Mr. Volchuck died March 18 at Holy Cross Hospital. He’s survived by his daughter, Anna, and his son, Leon.

Other notices would feature bible verses. Occasionally there would be a line or two of bad poetry or some clip art selected from a binder that was kept at the front desk.

Some death notices would give a bit more information about the person than just the names of their spouses, children, and grandchildren. For example, Jan Kowalski played football for University of Detroit and worked at GM for 30 years.

My job was to put each death notice into a standard format, get the facts and spelling right, and have it all ready to go to paste up (the paper was pasted up when I first started working there) in time for the Tuesday night press run.

The structure of death notice had been the same for the entire 75+ year history of the paper: Last name, first name, middle initial, location, date of death, survived by wife (nee maiden name), children, grandchildren, location and date / time of services.

Although the policy was to stick to the standard format and keep it as dry as possible, I would routinely include as much information into each death notice as I could. A death notice is a very different thing, with a very different purpose, from an obituary. But, I treated each notice as an opportunity to try to fit an obituary into around 50 words.

The challenge of squeezing human details or touching words into whatever small amount of space was left after listing the grandchildren was one that I was particularly fond of and good at.

The readership skewed towards elderly Polish-Americans. They were notorious gossips and wanted to know everything about everyone else’s troubles, illnesses, and ultimate undoing. The paper, however, had a policy of not printing the cause of death.

I was a 22-year old on a break of indeterminate length from college. Full of unearned self-assuredness, I argued with the editor-in-chief and publisher — who had a collective 40+ years of newspaper experience between them — that the cause of death should be listed in death notices whenever it’s included on the form.

Death notices were one of the most-read parts of the paper in this community. Listing the cause of death, I argued, would make the notices even more popular. The publisher considered it tacky to mention the cause of death, and pointed out that doing so would require additional research and permissions from survivors. I eventually saw that the trouble of printing the cause of death wasn’t worth the effort, and my crusade for openness ended there.

From this first experience with being published and having my writing distributed I learned to be concise, to always be thinking about the audience, and to do quality work while balancing the effort and rewards. These are vital skills for any writer to have, and I would encourage anyone who is just getting started as a writer to spend some time practicing the art of writing death notices.